As announced in the previous post, there will be from now on once in a while posts written by guest scholars, both junior a senior. This post has been written by Leonardo Ridolfi of the IMT School for Advanced Studies, Lucca. You can find Leonardo’s most recent working paper here.

The French economy in the longue durée. A study on real wages, working days and economic performance from Louis IX to the Revolution (1250-1789)

This work addresses a gap in the literature concerning living standards in pre-industrial France.

While traditionally research had an eminently localized character, focusing on the experience of specific regions or what might be called “local economics,” still to date, there is no consolidated understanding of the long-term development of wages and prices from a broader national perspective.

Building and improving upon the precious contributions offered by the many compilers of wage and price data in France, this study is an attempt to provide a solid empirical characterization of the principal macro-economic aggregates of pre-industrial France and trace the main contours of economic growth in the country from the phase of early state formation to the Revolution.

Delving into the vast set of secondary and printed primary sources, the first section presents new series of real wages for male agricultural and construction workers in France from 1250 to 1789 (now updated to 1860) following Allen (2001)’s barebones basket methodology.

The analysis highlighted three main issues.

First, our series offer little support to the argument that there were appreciable long run improvements in living standards for French wage earners before the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, real wages displayed no substantial trend improvement between the thirteenth and the mid-nineteenth century.

Second, the estimates reveal that the period 1350-1550 saw the rise and consolidation of a real wage gap between France and England as well as other leading European cities. Still in the decade prior to the Black Death the real wage differential between French and English workers of the construction sector was remarkably low. A century later, in the 1450s, French building labourers had between about 25 and 40 percent less of the income of their European counterparts.

Comparing real wages of French farmers to those of their English counterparts I found a similar pattern and few traces of a French “golden age” of labour. Indeed, after a first phase of rapid expansion following the Black Death, by the1370s real wages grew less and for a shorter period than elsewhere in Europe where the welfare gains consolidated almost until up the 1450s. At a more disaggregated level, similar trends are discernible by comparing Paris to London.

As a first step, I decomposed the proximate causes of this gap between prices and wages. I found that France and England witnessed similar deflationary trends between the 1370s and the 1450s. Yet, it was the decline of French silver wages (apparently driven by falling production and reduced labour demand especially during the worst phases of the Hundred Years War) and the contemporaneous increase of English salaries, that explain the “dampened” Malthusian cycle of real wages in France as opposed to the “full” Malthusian cycle experienced by England and Central-Northern Italy.

Figure 1: Real wages

Notes and Sources: French labourers: this study (updated version of the thesis). England: Clark (2005).

Finally, even if demographic data before the 1550s are fragmentary, it is possible to argue, consistently with the Malthusian interpretation, that the dynamics between real wages and population was characterized by a long-lasting inverse relationship. Nevertheless, while this mechanism appears to hold in general, at least by the mid-seventeenth century one can detect a weakening of the inverse relationship. Indeed, the long phase of demographic expansion that brought population almost to triple between the 1600s and the mid-nineteenth century, was paralleled by a mild decrease or a substantial stagnation of real wages.

The second section provides a broad characterization of working time in pre-industrial Europe concentrating on three dimensions of time: the calendar working year corresponding to the calendar year net of general holidays and religious festivities; the actual working year and the implied working year defined as the annual number of days of work required by a male breadwinner to provide for a notional family of five components (Allen and Weisdorf 2011).

Due to the dearth of compelling evidence on work intensity for workers employed in agriculture, I looked at the experience of construction workers on site providing new estimates of trends in calendar, actual and implied working year in France and England from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century.

By analyzing the joint evolution of these three dimensions of time and comparing the patterns of change of time-use, and their response to variations in the institutional and market conditions, I identified two distinct regimes of industriousness featuring France and England in the pre-industrial era.

In France, the annual number of days required by a male breadwinner to provide for his family (the implied working year) was greater than the actual number of days worked per year, meaning that women and children’s labour force participation as well as the presence of additional sources of non-labor income were necessary to assure the basic levels of consumption. This implies that expansions in the offer of labour were primarily driven by raising inflation and economic hardship (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The French case

Sources: Calendar, actual and implied working year: this study.

Notes: Surplus (deficit) labour input: The positive (negative) difference between actual and implied working year (shaded area).

By contrast, I found evidence of the existence of two phases where English regular construction workers supplied more days of work to the market than required by basic household subsistence (Figure 3).

The first episode occurred between 1400 and 1500, while the second corresponds to the industrious revolution originally described by De Vries (2008).

Several hypotheses are discussed to shed light on the origin of these phases of surplus labour input and their implications on the structure of consumption and production. These episodes differed in two fundamental ways.

First, they originated from different dynamics.

Indeed, the episode of surplus labour input located by De Vries in the seventeenth century England and the Low Countries, derived from an upsurge in actual workloads and a contemporary drop of work requirements necessary for family subsistence in a context of progressive expansion of the frontier of working possibilities.

On the contrary, the episode of surplus labour input detected in the post-plague period was characterized by the contemporary reduction of actual, calendar and implied working year.

Received wisdom would suggest that workers should have totally (or in large part) compensated the post-plague increases in real wage rates by reducing labour supply of approximately the same amount consuming a considerable proportion of their augmented purchasing power in the form of leisure (Blanchard 1994). However, actual workloads decreased much less than implied by the contemporary increase in real wage rates. This incomplete adjustment, that reflected a rather inelastic labour supply of construction workers, could depend on two main factors.

First, the existence of technical requirements and institutional settings, including the rhythm of the construction process, the rests dictated by calendar working year as well as the recruiting schemes of contractors and the organizational forms of entrepreneurs, limited voluntary reductions of actual workloads.

Second, the incomplete response of actual workloads could reflect the rise of a new attitude toward higher quality consumption from an increasing share of workers (seemingly skilled and urban) that was “aping the lesser gentry” (Dyer 1988).

In this respect, these episodes had different implications for the relationship between labour offer, consumption and production.

Indeed, the phase of surplus labour input in the seventeenth century England was seemingly related to a consumer revolution (Allen and Weisdorf 2011) and could be thought of as a transition from traditional consumption cluster to a broader and more modern one that included colonial products and luxuries (De Vries 2008).

The episode of surplus labour input in the late medieval England was not marked by more and new items entering the basket but seemingly ran in parallel with a relocation of consumption choices within the horizon of traditional consumption that reflected structural changes in the economy after the Black Death and the aspiration of a growing share of population for higher alimentary standards less dependent upon cereal-based and lower quality foodstuff (Dyer 1988).

From the production side, while the seventeenth century phase of surplus labour input saw the rise and consolidation of new sectors outside agriculture, the first episode (seemingly did not cause but) coincided in time with a shift of agriculture from arable to pasture. This process is consistent with a large body of empirical evidence documenting changes in alimentary regimes during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Figure 3: The English case

Sources: Calendar year: this study. Implied working year: Allen and Weisdorf (2011). Actual working year: Period 1300-1559: this study. Between 1560 and 1732, Clark and Van DerWerf (1998) and by 1750 Voth (2001) as reported in Table 2 of Allen and Weisdorf (2011).

Notes: Surplus (deficit) labour input: The positive (negative) difference between actual and implied working year (shaded area).

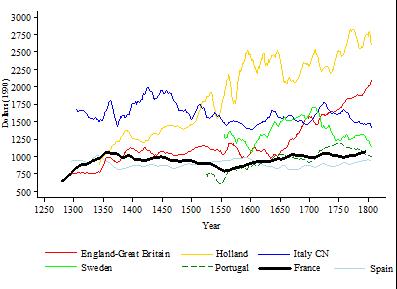

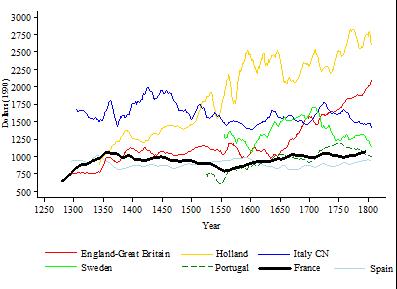

Finally, in the last section I present new estimates of agricultural and total output per capita in France between 1280 and 1789 using the demand side approach. The study suggests that GDP per capita displayed no substantial trend improvement over this period. At the death of King Philip the Fair in 1314, France was a leading economy in Europe and output per capita averaged 900 dollars per year. Almost five centuries later, at the beginning of the 18th century, this threshold was largely unchanged and GDP per capita was slightly above 1000 dollars, about half of the level registered in England and the Low Countries (Figure 4).

These estimates document quantitatively and in the aggregate what was previously known only qualitatively or for some regions by the classic works of the French historiography (Goubert 1960; Le Roy Ladurie 1966) thus offering support to Le Roy Ladurie (1977)’s characterization of the pre-industrial French economy as a stagnating, growthless system.

Nevertheless, GDP per capita was highly volatile and experienced multiple peaks and troughs alternating phases of economic crisis to periods of economic expansion. These include the “efflorescence” of economic growth that took place between the 1280s and the 1370s and the growth trend since the mid-16th century that ran in parallel with the consolidation of the French state and the opening of new trade routes from Europe to Asia and the Americas.

Overall, our estimates suggest that the evolution of GDP per capita in France can be suitably interpreted as an intermediate case between the successful example of England and the Low Countries and the declining patterns of Central-Northern Italy and Spain. Being neither a southern country nor a northern one, the growth experience of France seems to reflect this geographic heterogeneity.

Figure 4: GDP per capita in Europe

Sources: England: Broadberry et al. (2011); France: this study; Holland: van Zanden and van Leeuwen (2012); Italy: Malanima (2011); Portugal: Palma and Reis (2016); Spain: Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura (2013); Sweden: Schön and Krantz (2012).

References

Allen, Robert C. “The great divergence in European wages and prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War.” Explorations in economic history 38, no. 4 (2001): 411-447.

Allen, Robert C., and Jacob Louis Weisdorf. “Was there an ‘industrious revolution’ before the industrial revolution? An empirical exercise for England, c. 1300-1830.” The Economic History Review 64, no. 3 (2011): 715-729.

Álvarez‐Nogal, Carlos, and Leandro Prados de la Escosura. “The rise and fall of Spain (1270-1850).” The Economic History Review 66, no. 1 (2013): 1-37.

Blanchard, Ian. Labour and Leisure in Historical Perspective, Thirteenth to Twentieth Centuries: Papers Presented at Session B-3a of the Eleventh International Economic History Congress, Milan, 12th-17th September, 1994. No. 116. F. Steiner, 1994.

Broadberry, Stephen et al. “British Economic Growth, 1270-1870: An Output-Based Approach”, London School of Economics, 2011. http://www2.lse.ac.uk/economicHistory/whosWho/profiles/sbroadberry.aspx.

Clark, Gregory, and Ysbrand Van Der Werf. “Work in progress? The industrious revolution.” The Journal of Economic History 58, no. 3 (1998): 830-843.

Clark, Gregory. “The condition of the working class in England, 1209–2004.” Journal of Political Economy 113, no. 6 (2005): 1307-1340.

De Vries, Jan. The industrious revolution: consumer behavior and the household economy, 1650 to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Dyer, Christopher. “Changes in diet in the late middle ages: the case of harvest workers.” The Agricultural History Review (1988): 21-37.

Goubert, Pierre. Beauvais et le Beauvaisis de 1600 à 1730: contribution à l’histoire sociale de la France du XVIIe siècle: atlas (cartes et graphiques). Paris: SEVPEN, 1960.

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel. Les paysans de Languedoc. 2 vols. Paris: SEVPEN, 1966.

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel. “Motionless history.” Social Science History 1, no. 2 (1977): 115-136.

Malanima, Paolo. “The long decline of a leading economy: GDP in central and northern Italy, 1300-1913.” European Review of Economic History 15, no. 2 (2011): 169-219.

Palma, Nuno and Reis, Jaime. “From Convergence to Divergence: Portuguese Demography and Economic Growth, 1500-1850” (September 13, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2839971 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2839971

Schön, Lennart, and Olle Krantz. “The Swedish economy in the early modern period: constructing historical national accounts.” European Review of Economic History 16, no. 4 (2012): 529-549.

Van Zanden, Jan Luiten, and Bas Van Leeuwen. “Persistent but not consistent: The growth of national income in Holland 1347-1807.” Explorations in economic history 49, no. 2 (2012): 119-130.

Voth, Hans-Joachim. “The longest years: new estimates of labor input in England, 1760-1830.” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4 (2001): 1065-1082.