Here’s a new paper by Hélder Carvalhal and I, the first outcome of this project, which is funded by ESRC. (The project website is here.) The paper is also available as a CEPR discussion paper.

Here’s a new paper by Hélder Carvalhal and I, the first outcome of this project, which is funded by ESRC. (The project website is here.) The paper is also available as a CEPR discussion paper.

This conference recently took place in Manchester.

Interviews with the keynotes are available here.

DAY 1

Leigh Gardner

Hélder Carvalhal

Soeren Henn

Leonard Wantchekon

Rebecca Simson

Cal Links

Marlous van Waijenburg

DAY 2

Jacob Weisdorf

Guilherme Lambais

Marvin Suesse

Pablo Fernández Cebrián

Leonard Wantchekon giving a presentation about the Africa School of Economics

Steve Broadberry, Rebecca Simson, and Pablo Fernández Cebrián discussing economic growth and development in Africa

Ellen Hillbom

Zhexun Mo

Leandro de Magalhães

Gareth Austin

At its manufacturing peak, Stockport (near Manchester) had as many as 30 hat factories. Of course, the days when most men wore hats are gone, and the North has now de-industrialized, too. I’ve written before in this website about industrial heritage in the North, such as the Quarry Bank Mill, or the Bolton Steam museum.

I recently visited the Hat Works, a former factory in Stockport, now turned museum. The museum was very well put together, explaning the manufacturing process of hats in detail. Interesting examples include how the usage of mercury would create health problems to some workers, leading to behavior that led to the expression “mad as a hatter”. The guide was the amazing Lisa Ward, who tells her story to the BBC here.

Close to the museum, stands also the remarkable 1840 stockport railway viaduct, and WWII-era air raid shelters which protected locals during the Blitz.

Lancashire and nearby regions obviously have much industrial heritage associated with one of history’s most important events, the First Industrial Revolution, which was associated with the appearance of modern economic growth in England, earlier than any other region in the world. I have written here before about the Quarry Bank Mill and the Paradise Mill. Last weekend, I visited the Bolton Steam Museum, which was great. Here are some pictures.

As readers of this blog know, I take every year my economic history students to the Quarry Bank Mill near Manchester: a large and important cotton factory of the First Industrial Revolution.

But of course, the Manchester region also had other clusters, such as pottery cluster in Stoke-on-Trent (affectionately known as “The Potteries”), and a silk cluster in the region of Macclesfield (where a couple of modern silk-related factories in fact still operate today).

So, in a recent weekend, I visited the Silk Museum and Paradise Mill in Macclesfield. The Paradise Mill had its origins in the early nineteenth century and operated until the 1980s. Visiting was a great experience, and I share some pictures here.

The raw input:

Some general info:

Making the punch cards. These binary instructions define the patterns, and of course influenced modern computers:

An example of the resulting pattern (notice the small upper-left square):

Notice how detailed and fine this could become:

The machines:

The “code” and resulting pattern in a pillow:

Feeding the “code”:

You can hear my participation in Dan Snow’s History Hit podcast here. Thanks to Dan for the invitation.

For anyone interested in knowing more, this is the paper (joint with Patrick O’Brien) recently published in the EHR and motivated this participation, available in open access here. This was the main paper underlying our discussion, though in the podcast Dan and I also discuss monetary politcy and the role of central banks in more recent times.

p.s. I heard the recording and take the opportunity to mention that around minute 17.43, when I say “sixteenth century”, I obviously meant to say “eighteenth century”. And just before the break when I said “lending”, I meant “borrowing”: though this should be clear from the context. That was my fault of course: perils of live recordings!

I’m delighted to announce that I have been awarded a ESRC New Investigators grant for the project: “Measuring the Great Divergence: a study of global standards of living, 1500-1950”. A call for a postdoc will open soon. In this thread I briefly give details about the project. Stay to end for some juice about Portugal’s funding agency, FCT, which had twice rejected a similar proposal of mine previously (and for less money, €250K instead of the £300K that I was now awarded).

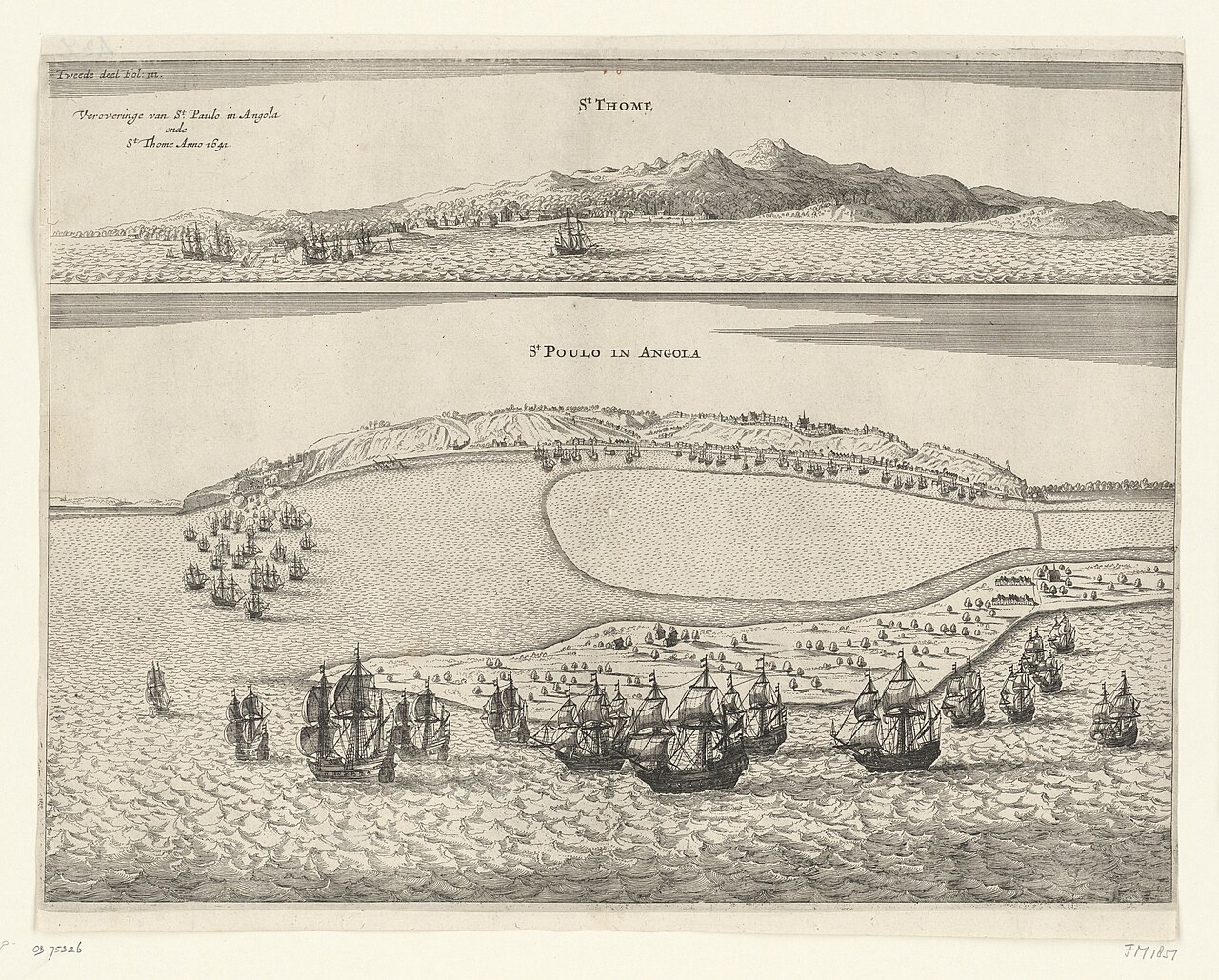

We will use archives in Portugal and its former colonial sites to collect five centuries of real wages and welfare ratios. We will focus on locations such as Luanda in Angola, the Mozambique island, Goa in India, and Macao. We will know their comparative development and inequality levels over time.

Our data will be the earliest quantitative welfare comparative information for several regions in Africa, for example. Hence the project will open new avenues for understanding the causes and timing of the ascendency of Europe.

Some scholars argue that slavery and colonialism were what made Europe rich – and kept Africa and other regions of the world poor. We will, for example, be able to see the evolution of the welfare levels in Africa before (and during) any large-scale European presence and demand for slaves. Portugal’s sources go two centuries further back than any others, and cover regions such as Angola from which a disproportionate amount of slaves were taken.

We will produce a set of outputs for academically interested stakeholders and the interested general public. These will include a book to be published by a major publisher and three articles for international peer-reviewed academic journals, plus dissemination events, etc.

Now a personal anecdote about my attempts at getting this funded. This was my third attempt. I tried twice before with a similar project via FCT, Portugal’s research funding agency. It was rejected once by a History panel, and once by an Economics one. It got funded at my first attempt with ESRC.

The comments provided by FCT were factually incorrect, and pathetically bad from a scientific standpoint.

– claims made in direct contradiction to the project’s abstract

– claimed I was “too junior” to be the PI (no rules placed any age constraint, and my CV is top compared with any full professor in Portugal; so this is an example of Portugal’s gerontocracy, and probably illegal).

The History panel was in fact mainly composed of archeologists (this is public information) and funded instead of mine, projects such as (again this is public information which can be found online):

“A aldeia histórica de Idanha-a-Velha: cidade, território e população na antiguidade (séc. I a.C. – XII d.C.) – The historical village of Idanha-a-Velha: city, territory and population in ancient times (first century BC. – twelfth century AC)”

“O Percurso Cromático do Azulejo Português – The Chromatic Journey of the Portuguese Azulejo”

“Pensa em grande sobre as pequenas vilas de fronteira: Alto Alentejo e Alta Extremadura leonesa (séculos XIII – XVI) – Think big on small frontier towns: Alto Alentejo and Alta Extremadura leonesa (13th – 16th centuries)”

“Na espessura das paredes e na profundidade do solo – In the width of the walls, in the depth of the soil”

Undeterred, I tried FCT again the following year. To avoid the History panel, I tried Economics, and got these comments:

– contributions the proposal not clear

– only one study country (Mozambique) fits into East Africa (!!)

– The PI (…) has insufficient expertise and the team isn’t sufficently international

In fact, I have published several papers on long-run standards of living (see for instance this), and the proposed team was composed of the PI, me (having my main affiliation abroad) and only two other Portuguese scholars with affiliations in Portugal; the latter two were experts in the sources, located in Portugal and its former colonies. All the other 4 proposed team members are nationals of other countries with affiliations in foreign institutions and all were experts in these types of sources.

To be fair, you sometimes get idiotic comments from referees at good journals too. But FCT does this far too consistently. A key source of criticism to FCT concerns not only the bad scientific quality of the comments one gets but also the fact that one does not have a chance to respond. In ESRC, I got 4 referee assessements of my project, and had a chance to respond to clarify any misunderstandings. Two of those 4 classified this project as “outstanding” along all categories and there was really nothing to respond to; while the other two had minor criticisms, and I got a chance to clarify whether these were misunderstandings. This led to much more fairness and transparency of the process. By contrast, FCT hires supposedly “international experts” – but really most are substandard researchers from often terrible universities – perhaps because it pays them badly, so no one better wants to do the work. The result is what it is: they send their assessment, and if you appeal the rejection, it goes to the same people again (and they just double down on the nonsense).

Anyway, the moral of the story is of course: Starting out is hard, but don’t give up! I’m now looking forward to looking deep into the comparative quantiative history of Africa and other regions of the world.

Update: this post has been updated in 2022, follwing the release of the new version of our paper.

A new paper is out, with the title “Stunting and wasting in a growing economy: Biological living standards in Portugal during the Twentieth Century”. You can find the CEPR (gated) version here, and an open access version here.

In this paper, we document the remarkable progress that happened for the living standards of children and young adults in Portugal during the second half of the 20th century. Portugal’s real income per head grew by a factor of eight during the second half of the twentieth century, a period of fast convergence towards Western European standards of living. To which extent was there a reflection of this progress on the wellbeing of people?

We use a new sample of 3400 children to document trends in the prevalence of stunting and wasting. We additionally use a sample of 26,000 young adult males covering the entire country which shows similar trends.

We find that the prevalence of stunting and wasting fell quickly from the 1950s, for both males and females. Natually, 20 year-olds lagged behind children and the county also lagged behind Lisbon. But life improved for everyone, and it did so for females as much as for males. Stunting and wasting were considerably higher for infants than children (as we show in the paper), at least partly due to selection of survivors. Child mortality was high but steadily declining over our period. For children (2 to 10 years of age), for example, the prevalence of wasting (being underweight, usually due to malnourishment or diseases) fell sharply. The results for stunting (children well below the normal height for a given age) are similar.

Comparison of stunting in Lisbon vs. Portugal for 20 year-old males show that standards of living were higher in Lisbon, but there were improvements over time in the country overal over time, with the timing of the improvements in Lisbon ahead of elsewhere:

In the paper, we discuss the causes of these trends: changes in income and public policy which affected the ontogenetic environment of children. The income and health improvements which happened in Portugal over the second half of the 20th century led to the improvements that we document. From around 1950, infrastructure improved considerably, both with regards to water access, sewage, and quality of dwellings. This decreased the incidence of diarrhea and other digestive diseases that commonly affect children. Infant mortality due to digestive diseases up to 3 y.o. fell, and literacy levels among children also steadily rose from the late 1920s. Later, these became more informed parents, who presumably took better decisions.

The macroeconomic progress which occurred in Portugal during the second half of the 20th century was associated with considerable improvements in the living standards of ordinary citizens including children and young adults. That progress began under the Estado Novo regime and further continued under democracy. As a result of this joint progress, Portugal was transformed during the 1945-1994 half century from a country with dismal development outcomes into a modern developed country as far as health outcomes are concerned.

Updated September 2021.

This paper is now published in the Journal of Economic History. [open access version here].

Market fragmentation prevailed in China during its Republican and Nationalist periods. That is what most of the existing literature says, at least: domestic markets were segmented due to a largely self-sufficient peasant economy, backward transport, and low state capacity. The latter led to political instability and various warlords controlling different regions of the country. As a consequence, port cities and the countryside had independent markets, which limited economic growth.

In a new CEPR discussion paper (written by Liuyan Zhao of the school of economics of Peking University and myself), we test for money market integration in China during 1920-1933 using a new dataset of daily domestic exchange rates. We consider ten Chinese cities, all of which were on a silver standard, for 1920-1933. We find that despite political instability, domestic financial markets were highly integrated in much of the country.

With the exception of the period of the Northern Expedition (09/1926-12/1928), the

exchange-market efficiency of the Chinese silver standard among China’s main economic hubs was not much different in magnitude to that of the classical Dollar-Sterling gold standard before World War I. We hence conclude that there was a substantial degree of Chinese financial markets integration before the Sino-Japanese War, and we attribute this fact to technological advancements such as the rapidly explanding railway and telegraph lines, to monetary innovations, and to China’s low labor costs which contributed towards low transportation costs. Most of these factors were of Western origin, and spread due to Western influence and presence in China, even if that presence also arguably represented a threat to Chinese sovereignty. However, remote cities in South China not under central government control were less integrated.

Our study carries implications for the historical understanding of market integration

at a time of political disintegration during the Warlord Era and the early years of the

Nanjing Decade. We find that the Chinese silver standard in the most advanced parts of the country was remarkably efficient at this time. However, political turmoil and weak state capacity implied that Chinese economic development in parts of the country was kept in check.

A open access version of our paper is here. The CEPR discussion paper version is here.

Economic history matters for big debates. This can be true of even historical national accounting work which to some observers can appear to be as dry a topic as any can be. Here’s an example of why it matters.

In this interview with Tyler Cowen, the notable historian Adam Tooze mentions (from around minute 32) how in writing his celebrated book “Wages of Destruction: the making and breaking of the Nazi economy”, he was critically influenced by the work of top economic historians Angus Maddison and Stephen Broadberry. Their work on productivity comparisons between the USA and Europe, as well as between the UK and continental European countries was of fundamental importance to the formulation of Tooze’s innovative arguments in his book, which relied in part on the rejection of anachronistic assumptions about German economic power prior to (and during) the war.

Tooze’s book rationalizes some of Hitler’s strategic military actions, such as the invasion of the Soviet Union, arguing that it was an ideological but also calculated move to grap resources in antecipation of war with all-mighty USA. The book has at times been criticized for downplaying the role of the UK, but is undeniably brilliant, and it deservingly won the Wolfson History Prize.

Watch the interview here: