This post continues the highlights series. The author is Per F. Andersson, who is a Lecturer at Lund University, and an expert in Comparative Politics, Institutions, and Taxation. He is responsible for the text below, and the amazing dataset he mentions was was put together both by him and by Thomas Brambor.

The data and codebook are available at: https://www.perfandersson.com/data.html

What can we learn from two centuries of budget data? Introducing the “Financing the State: Government Tax Revenue from 1800 to 2012” dataset – Per F. Andersson

The history of the state is closely linked to the history of taxation. Austrian sociologist Rudolf Goldscheid held that “the budget is the skeleton of the state stripped of all misleading ideologies”, and Joseph A. Schumpeter went even further, famously stating that “The spirit of a people, its cultural level, its social structure, the deeds its policy may prepare – all this and more is written in its fiscal history, stripped of all phrases. He who knows how to listen to its message here discerns the thunder of world history more clearly than anywhere else ([1918]1991 p. 101).“ If Schumpeter and Goldscheid were right, much can be gained from studying taxation during the last two centuries, an era that saw dramatic changes not only in the extent of taxation but also in economic and political organization.

Given the importance of taxation for understanding politics, state capacity, and economic growth, it is surprising that there is no historical cross-country dataset over government finances. In this post I present an attempt by me and Thomas Brambor to provide this information. The dataset provides information from 31 countries: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela from 1800 (or independence) to 2012. In other words, it includes all South American, North American, and Western European countries with a population of more than one million, plus Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and Mexico.

We make three main contributions. First, we move beyond previous historical studies which focus on Western Europe by including North America, all major countries in South America, and Australia, Mexico, New Zealand and Japan. Second, in contrast to existing modern datasets, usually covering a large number of countries but only for a few decades, our dataset goes back to the early nineteenth century. Third, while previous efforts have concentrated on overall revenue or contrasting direct and indirect taxes, we provide more detailed information allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the rise of the modern tax state.

This post begins with a short description of how the dataset was put together, and how it differs from previous efforts (for longer discussion see the online codebook available at: https://www.perfandersson.com/data.html). In the second part of the post I demonstrate how the data can be used to explore changes in the size and composition of government revenue during the last two centuries.

Constructing the dataset

The dataset contains information on the public finances of central governments. We focus on tax revenues, defining taxes as compulsory and unrequited levies by the government. The information on tax revenue is presented as a share of the total budget and as a share of total domestic product. We have divided tax revenue from the central state into several categories. First, we are interested in the shares of total revenue coming from direct and indirect taxes. Further, we measure types of direct taxes, namely taxes on property and income. For indirect taxes, we separate excises (taxes on specific goods, such as salt or tobacco), broad-based consumption taxes (such as value-added tax), and taxes on international trade (a complete list of variables and their definitions is available in the codebook.)

Collecting data for a large number of countries over long time spans presents difficult issues regarding measurement and consistency. The overall goal of the data collection has been to create long time series that are internally consistent within a country over time and that connect to contemporary datasets which in turn allow easy continual updates in the future. When different sources of data are combined, there need to be decisions about how to decide which sources to use and how to judge their quality. In addition, using and combining different sources has the potential to introduce measurement error and potentially bias the constructed estimates. In the codebook we describe in detail the decisions about how we integrated disparate sources, and also address a few issues that are relevant for analysis based on these data.

Comparison with related efforts

Previous research using historical tax revenue data either relies on information with a long historical coverage (some even long before 1800, e.g., Dincecco 2009, Karaman and Pamuk 2013) but for a few number of countries — usually Western Europe (Aidt and Jensen 2013), sometimes adding English-speaking off-shoots and Japan (Tanzi and Schuknecht 2000) — or a wide geographic coverage but only for the most recent decades (e.g., Prichard et al. 2014). These efforts rarely provide yearly data (e.g., Tanzi and Schuknecht 2000), or present information only on the size of government (Mauro et al 2013, Karaman and Pamuk 2013).

Many recent papers still rely heavily on Mitchell (2007) (e.g., Beramendi et al. 2019; Lee and Paine 2020). For various reasons we have a different approach which we believe has much to contribute.

Instead of taking existing cross-country databases (such as Mitchell) at face value, we took great pains at comparing and evaluating different sources – often cross checking them with country-specific sources – in order to find as reliable data as possible. During our work we discovered that Mitchell in particular is often unreliable. When comparing the information provided in his volumes with contemporary, high-quality, country-specific data we found two main causes for concern. First, Mitchell is often inconsistent in the way budget items are coded or even which parts of government budgets are presented, which causes problems when interpreting changes over time and across countries. The second problem is that the subcategories of revenues in Mitchell (e.g., direct and indirect taxes) at times sum to more than a hundred percent, which suggest underlying issues in the aggregation process. For these reasons, among others, we have tried to minimize our use of Mitchell as a source, and when we use it, we try to find ways of validating the trustworthiness of his estimates (for example by using country-specific sources).

Overall, a substantial part of our dataset comes from country-specific sources, all listed in the codebook. For users who wish to explore the data in more depth, we also provide detailed information by country allowing analysts to scrutinize by variable which sources were used for every year.

Exploring the data

To begin with, Figures 1 and 2 below present total tax revenues and the share coming from direct and indirect taxes (averages for all countries in the dataset). The figures show how the overall size of the state grew from about six percent of GDP in the nineteenth century to almost twenty percent in the 2000s. During the same period states went from financing themselves mainly through indirect taxes to a more even mix of direct and indirect taxes.

Figure 1. Central Tax Revenue/GDP

Figure 2. Share of Direct and Indirect Tax Revenue

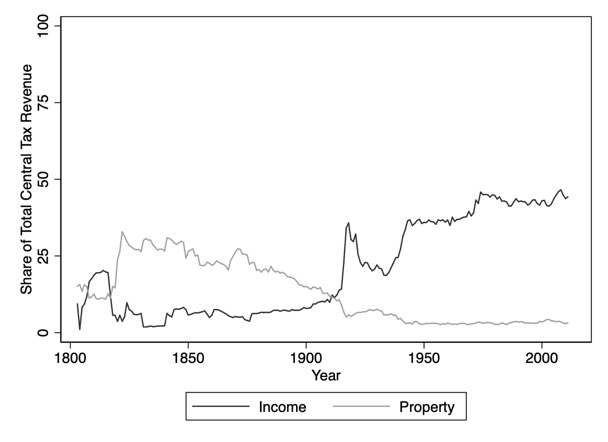

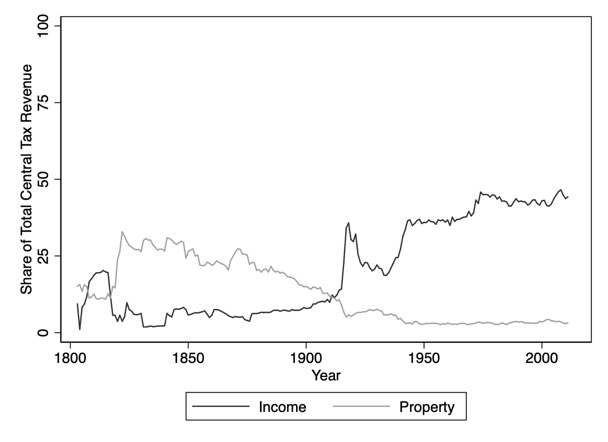

However, this general development hides important changes within the categories of direct and indirect taxes. As Figure 3 shows, excises and taxes on international trade were the main sources of indirect tax revenue in the nineteenth century, while broad-based consumption taxes – such as value-added tax – became more important in the late twentieth century. Figure 4 shows the evolution of direct taxes in the same period, documenting how property taxes — an important part of budgets in the nineteenth century — were superseded by income taxes in the twentieth century.

Figure 3. Indirect Taxes.

Figure 4. Direct Taxes.

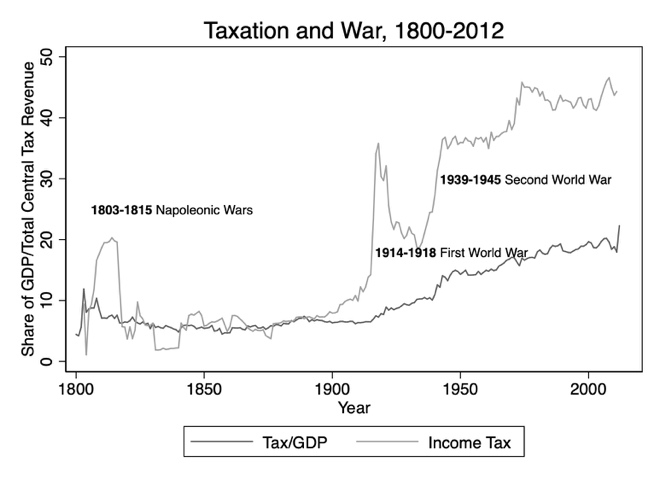

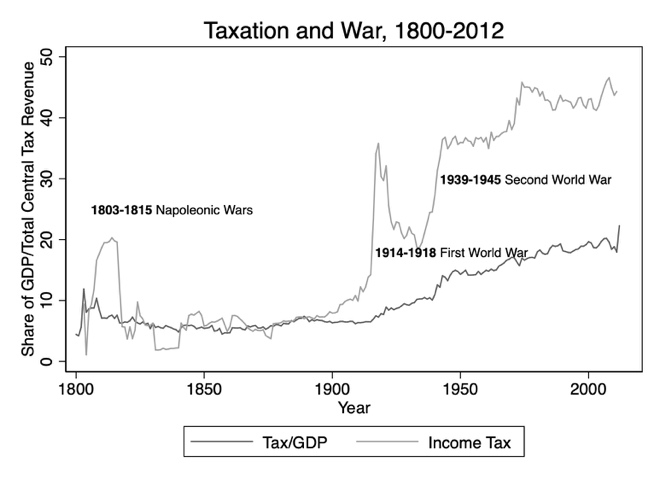

It is also interesting to observe what happened to taxation around the world during and after major international conflicts. Figure 5 below show total revenues and the share of income taxes — which is considered to be a good indicator of fiscal capacity (e.g., Rogers and Weller 2014) — and three major conflicts: the Napoleonic Wars, the First World War, and the Second World War. While the number of countries for which we have data (and some did not exist at the time) is lower during the Napoleonic wars, it is still interesting to note that the conflict is neither associated with a permanent increase in income tax share nor in the overall size of the state. The two world wars are different. After World War I, the average size of government remained higher than before the war, and this tendency is even stronger after World War II. Looking at the share of revenue coming from income tax, this tendency is much weaker after World War I: while the share increased dramatically during the war, it decreased after the conflict ended (but not all the way down to pre-war levels). In contrast, income tax revenues not only became hugely important during World War II, they also remained so afterwards.

Figure 5. Size of Government, Income Tax, and War.

Finally, one of the great strengths of our wide geographic coverage is that it allows for comparisons between regions. Figure 6 below shows the evolution of total tax revenues and income tax share between Latin America and Europe.

Figure 6: The Size of Government and Income Tax in Europe and Latin America

There are several interesting things to note. First, although Latin America does not experience an increase in the income tax share during World War I as Europe does, both regions experience an increase in income tax revenues around the time of World War II. Second, between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s, Europe and Latin America relied to a similar extent on income taxes. But after around 1975, the two regions diverge, both in terms of the income tax share and in terms of total tax revenues.

These are just a couple of examples of what can be explored using our dataset. In my own work I have looked into how democracy and urbanization affect the tax mix (Andersson 2018), how electoral systems condition the impact of ideology on taxation (Andersson 2019a), and how the adoption of taxes affects fiscal capacity and what types of states make these investments (Andersson 2019b). Thomas Brambor has investigated the legacy effect of non-democratic introductions of the income tax (Brambor 2016).

The data and the codebook are available at: https://www.perfandersson.com/data.html.

References

Andersson, Per F. 2018. “Democracy, Urbanization, and Tax Revenue.” Studies in Comparative International Development 53(1):111–150.

Andersson, Per F. 2019. “Power-sharing and Income Taxation in non-Democratic States.” STANCE Working Paper. Lund University.

Andersson, Per F. 2019. “Left-wing Tax Strategy Depends on the Electoral System.” Working Paper. Lund University.

Aidt, Toke ., & Peter S. Jensen. 2013. “Democratization and the size of government: Evidence from the long 19th century”. Public Choice, 157(3/4), 511-542.

Beramendi, Pablo, Mark Dincecco and Melissa Rogers. 2019. “Intra-Elite Competition and Long-Run Fiscal Development.” The Journal of Politics 81(1):49–65.

Brambor, Thomas. 2016. “Fiscal Capacity and the Enduring Legacy of the First Income Tax Law”. Unpublished manuscript: Lund University.

Dincecco, Mark. 2009. “Fiscal Centralization, Limited Government, and Public Revenues in Europe, 1650–1913.” The Journal of Economic History 69(1):48–103.

Flora, Peter, Franz Kraus, and Winfried Pfenning. 1983. State, Economy, and Society in Western Europe 1815-1975: The growth of industrial societies and capitalist economies, Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2012. “Government finance statistics (GFS).”

Karaman, K. Kivanc and Sevket Pamuk. 2013. “Different Paths to the Modern State in Europe: The Interaction Between Warfare, Economic Structure, and Political Regime.” American Political Science Review 107(3):603–626.

Lee, Alexander and Jack Paine. 2020. “The Great Revenue Divergence”. Working paper.

Mauro, Paolo, Rafael Romeu, Ariel Binder, and Asad Zaman. 2013. “A Modern History of Fiscal Prudence and Profligacy,” IMF working paper WP/13/5

Mitchell, Brian R. 2007. International historical statistics: Africa, Asia & Oceania, 1750- 2005, 5. ed., New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

, International historical statistics: Europe, 1750-2005, 6. ed., New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

, International historical statistics: the Americas, 1750-2005, 6. ed., New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prichard Wilson, Alex Cobham and Andrew Goodall. 2014. “The ICTD Government Revenue Dataset” ICTD Working Paper 19. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/ICTD_WP19.pdf

Rogers, Melissa Ziegler and Nicholas Weller. 2014. “Income taxation and the validity of state capacity indicators.” Journal of Public Policy 34(2):183–206.

Schumpeter, Joseph. 1991. “The Crisis of the Tax State”. In Joseph A. Schumpeter: The Economics and Sociology of Capitalism, ed. Richard Swedberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published in 1918.

Tanzi, Vito & Ludger Schuknecht. 2000. Public spending in the 20th Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.